Back in the stone age of telecommunications, Bulletin Board Systems, or BBSes were the meat and potatoes of the way we got online to literally "network" with other folks - post messages, up and downloaded files, and chat. You'd connect a modem to your computer, plug a phone line into it, set up your favorite terminal program dialer's phonebook list with your favorite boards, then dial out, log in, and do whatever you wanted to do.

Most BBSes were free, some were subscription-based. Some "kitchen table" boards could only handle one caller at a time, while others had many modems attached to them and could deal with multiple, simultaneous callers.

Then there were the commercial online services like CompuServe, GEnie, Delphi, BIX, People/Link, and AOL's ancestor, QuantumLink, to name a few. These services typically billed you each month based on how many hours you racked up online. Rabid, addicted users ran up enormous monthly bills, often hundreds of dollars, as they scrounged the services' libraries for software to download on whatever flavor of computer they had.

The commercial services were, for all intents and purposes, giant BBS systems. The Web didn't exist, so they boasted forums or clubs targeted to every kind of hobby or interest group you could name.

Back in those halcyon days, the terminal program was the tool you used to access BBSes and commercial services, and there were more different term programs for every computer platform than I can even name. Hundreds of them.

The longest software review I ever wrote for a magazine was a comparison of over a dozen different Amiga terminal programs. Everyone had his or her favorite. That review took more time, more testing, more phone calls than I even want to think about. I also authored the entire Amiga chapter for one of John Dvorak's Telecomm books. (In case you think he writes every word in all of his massive tomes, I've got news for you – he doesn't).

So the terminal program was an indispensable tool for me. And in one way, it still is.

In 1985 I started an online service for Amiga computer owners called AmigaZone which to this day is still in operation. One by one, the commercial online services named above either went away, or made it impossible to access them with a simple terminal program, as they implemented their own custom interfaces, forcing you to use their proprietary software to connect or do anything with them, such as AOL uses.

In came the Web and it all changed

Then in the mid 1990s, along came the Web, and everything changed. One by one, BBSes vanished.. became a thing of the past, and the Web Browser became the tool of choice, even necessity, to access online content. There wasn't a whole lot to do or see on the Web in its infancy. The Amazing Fish Cam. The White House's Web site. Tour the Louvre in Paris. But as the Web grew exponentially, the big money entered the scene.

The modem's in that heap, covered in dust

Hardly anyone uses dial-up modems and phone lines to get connected any more.. these days it's cable, or DSL, or a satellite dish.. operating at speeds we could only dream about back when a 1200 baud modem was fast, and cost a week's pay for most people.

Well, my AmigaZone service is still up and running, and has a Web interface, or members can Telnet into its BBS-style interface to read and post messages, up and download files, and chat live with each other, so it is, in fact, a hybrid system with both Web access and Telnet access to all the same content.

I get a lot of email from TreoCentral readers who ask "aren't you the same Harv who ran AmigaZone? I used to be a member!" And I get a kick out of telling them yup, that's me, and it's still up and running.

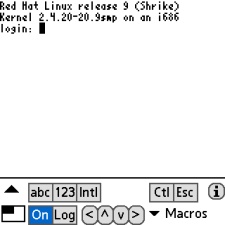

The UNIX shell and those alien commands

Besides "kitchen table" BBSes, many ISPs also offered their customers a UNIX shell account. Now it's beyond the scope of this review to explain what a UNIX shell account is, but in a nutshell, it's a text-only interface to a UNIX box you connect to and in which you type fairly obscure commands to run programs and use numerous tools to send and read mail with programs like Pine and Elm, read or post to tens of thousands of Usenet groups with TIN, browse the Web with the Lynx text-based browser, store and retrieve files of all description, and you do this by typing in sometimes obscure UNIX shell commands to perform these various actions, and a lot more.

Just like thousands of BBSes blossomed, then vanished over the years, the number of ISPs who still offer shell accounts has also dwindled, but they're still out there, I still have one, and maybe you do too.

The old Palm models required an optional modem, and a phone line to make a dial-up serial connection to reach these systems. A Treo doesn't since it IS its own "phone line" – all you need is a "terminal emulator" or Telnet client to connect, if you have a shell account somewhere.

The hunt begins..

Since AmigaZone is still alive and kickin', and I still have a separate UNIX shell account with the ISP that hosts it, I needed to source a full-featured app for my Treos to access both while away from my computer.

If you visit any of the usual sources of PalmOS freeware, shareware, or commercial programs, and search for "Telnet", you'll find very few choices. I tried a couple of different programs, none of which really cut it for me, either due to their age, lack of features, or ability to do things like handle IBM ANSI color text, or open up a "chat window" to type back and forth with my AmigaZone members in our live chat area.

After a lot of searching, downloading different programs, giving them a test-drive, getting disappointed, and ultimately junking them, I finally found a program with the capabilities to do what I needed it to do –access AmigaZone and all its features, AND my ISP's shell account from on my Treos from anywhere.

It didn't take long to settle on Conklin Systems' "CSOnline" – an extremely well-programmed, feature-packed, and professionally-supported VT100 / ANSI Terminal program and Telnet client in one.

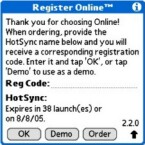

Generous demo

I took it for a trial spin – CSOnline's free demo mode lets you launch and use it either 40 times, or for 30 days, whichever comes first. After just a few uses, I decided "this is the one that does what I need to do" and registered it. The $34.95 registration price seemed pretty high for such a program, but like I said, the free Telnet apps I found just didn't cut it for me. In some cases, you get what you pay for. In this case, that old saw applies.

A powerhouse under 200k!

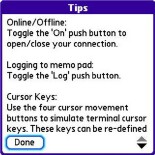

CSOnline is a tiny program, eating up just under 200k after installing its single .prc file onto a Treo. Conklin Systems has packed an enormous amount of power and features into such a small app, and there is abundant built-in help on every screen of its interface.

Despite its size, it's a VERY capable program, and boasts these (and many other)features:

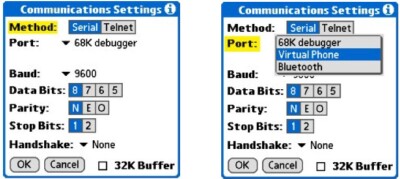

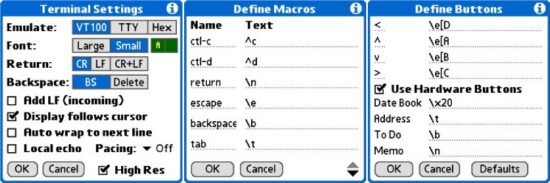

- Telnet, VT-102/ANSI, TTY and Hex Emulations

- Connect via Serial, IR, Bluetooth, 802.11 WiFi or Modem

- XModem, XModem-1K, and YModem send and receive of files with VFS

- Full 80 column display on a single screen (select hi-res handhelds)

- 80 x 24 display on low-res devices using a virtual screen

- Supports new serial manager and multiple virtual serial ports, CF cards, IR, etc.

- Large 32K buffer mode for data intensive applications

- Hex Terminal mode for serial debugging. See data in hex/ASCII format.

- Assigned custom key mapping of 4 tool bar buttons and 4 hardware buttons

- VT-100 special keys menu with PF1-PF4, DEL and BREAK

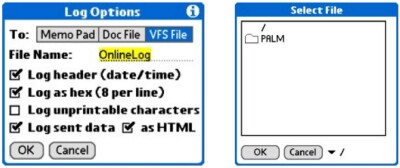

- Log incoming data (as text, hexadecimal and HTML) to: Memo Pad Entries (4K per record), 'Doc' File (to main memory), or VFS File (DOS text file on expansion memory)

There are features in CSOnline I'll probably never use, although it's nice to know they're there, should I need them.

Squint!

Reading 80 column text on a Treo's two inch screen can be a pretty painful experience, but Conklin has implemented the ability to change the font of the display via the "Large Font" checkbox in the "Display" dialog reached via the "Options" menu. This switches between a 7pt and 8pt fixed-width Minico font. The 7pt font allows Online to display 80 characters across the screen, greatly reducing the amount of scrolling required. There are no other font style choices, but believe it or not, as small as a 7pt font is on a Treo screen, it IS quite readable when the program is popped into hi-res mode with one of its preference toggles.

CSOnline is crammed with preferences and options, just some of which are shown in the screen shots in this review.

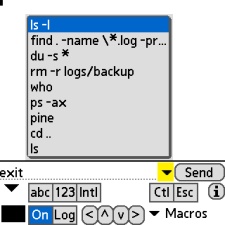

To give your flying fingers some relief, you can set up Macros for frequently-used strings of text or commands,

And customize the colors with a full-palette color picker to whatever makes you comfy - CSOnline lets you choose separate text and background colors that best suits yours needs or whim.

Over the decades, there have been a number of popular color schemes, from Green-text-on-Black (dedicated terminals) to White-on-Blue (Atari home computers) to Black-on-White 'paper' like schemes. There is no 'right' color so pick whatever works best for you.

As you set up connections to different host systems, you can configure a custom font / background color set for each one and CSOnline will remember it each time you connect to that system.

The program has a bank of user-definable buttons at the bottom of the screen – and / or you can program it to use your Treo's hardware buttons to perform different functions.

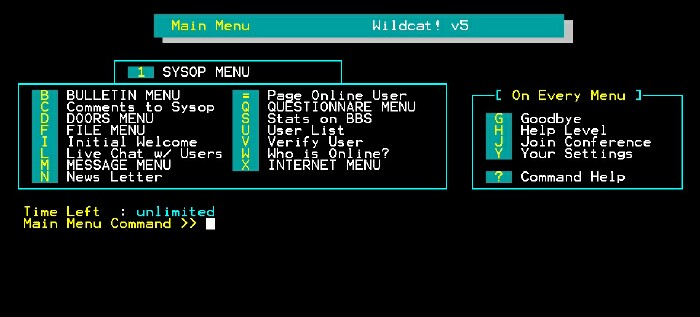

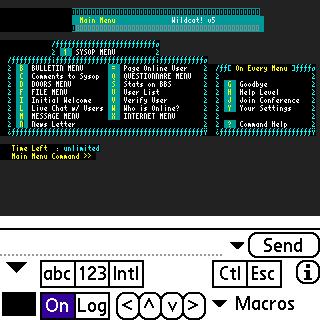

I really got a kick and a half using CSOnline to log into AmigaZone's IBM color ANSI BBS-style interface to check my mail, read and post messages, and especially go into our live chat area and yak with members who were online.

Unlike so many other Telnet clients, CSOnline's programmers even gave this beautiful little program a toggle-able "chat line" so one can enter text and then send it a line at a time, instead of out-going text mixing with incoming text in its main window. This is a feature I used to rant and rave about back in the days when I reviewed more Amiga terminal programs than I can even remember, and a feature lacking in most every other PalmOS Telnet client I tested.

I only had two gripes when using CSOnline with AmigaZone – it doesn't properly render IBM ANSI "line drawing" – check out the screen shots below for a comparison of what AmigaZone's main menu looks like on my favorite Windows Telnet client, "CRT" by VanDyke software, which I've used for eons, and CSOnline and you'll see what I'm talking about.

The other things lacking that I'd like to see implemented in CSOnline is Zmodem protocol, a buffered backscroll slider, a battery meter, a "keep the session alive by sending a carriage return every x seconds" to avoid time-out disconnects, and a time-online session duration clock. After discussing these wants with Conklin's support team, they said they'd put them on the to-do list for a future version.

This is a dual-pronged problem of the amount of screen space available for clocks and gauges, and the way PalmOS doesn't multi-task very well.. if you're using CSOnline and you want to see your battery level, you have to leave the program to view it, and thus lose your connection in the process, so after you run it again, you have to re-connect again. No big deal if you're using CSOnline while jacked into to your Treo's power supply, of course, but when operating on battery power only, I think EVERY program should have some kind of way of showing you how much juice you have left, even if it requires tapping a button or selecting a menu pull-down to see it.

Obviously, if you want full 80 column text on a tiny Treo screen, there's very limited space for other indicators or even a backscroll slider, however there ARE ways around these limitations -

Besides its excellent and copious built-in help on EVERY screen, CSOnline's manual comes with the program as HTML files which download in a .Zip package, and they explain, illustrate, and instruct you as to absolutely everything the app can do. A huge thumbs up to Conklin Systems for including an excellent manual, a Web site that fully describes the program, and a very generous free trial period.

Again, here's a company who obviously put a lot of time and care into what they're doing.

Next Page: Conclusion >>