User Opinions

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

| Thu May 3, 2007 - 9:44 AM EDT - By Harv Laser | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

It�s amazing how much we take photography for granted. You can walk into the nearest Wal-Mart and pick up a disposable film camera on the cheap, for as little as $2 and use it to take shots of your family vacation at Disneyland and get prints back in an hour, or snap an endless stream of photos and videos with your Treo�s built in camera and store them as long as you want on SD media. Truthfully, photos and videos are so commonplace in our society that it�s hardly imaginable to not think of having a few on us at any given time. Got any photos in your wallet or purse? 'Nuff said..

Filmographia, the art of making a sequence of thousands of tiny pictures move and dance for our ceaseless pleasure on the screen has its roots in ancient China. In those bygone days, (500 BC) the philosopher Mo-Ti first recorded the use of a method of reproducing an image using a small pinhole in a wall to focus light from the outside, which appeared as a projection on an opposing wall inside of a darkened room.

This concept was hardly a secret, as Aristotle used similar methods to observe solar eclipses in Ancient Greece, circa 350 BC � and if you ever made a "pinhole camera" out of a shoebox when you were a kid, so did you!

Up through the late Renaissance period scholars and artists made heavy use of what Johannes Kepler , the famous German astronomer, would later dub the camera obscura - (Latin for dark room).

This invention slowly shrunk in size, until the device was no larger than your average shoebox.. that one you made in school {{grin}}.. Other than adding a lens to focus a wider field of light, the ancient camera is little different than the ones we use today, though the invention of film to record the captured images didn�t occur until the early-19th century.

The first photographic recordings, and likewise the science behind them is largely credited to Nic�phore Ni�pce, who, in 1816, added a photo-sensitive paper to the camera obscura, finally shedding light on a way to permanently transcribe and save images of the world around him, though the finalized process didn�t materialize until a decade later in 1826.

Motion pictures, or movies were only a few years behind all these marvels, as their debut in 1890 shines as a milestone in our history when inventor Kennedy Laurie Dickson creates the Kinetograph for Thomas Alva Edison & Co. This design is the foundation of the modern motion picture camera and allowed one person at a time to play and view a movie on the companion Kinetoscope, player.

Though crude by comparison to other forms of projection, Kinetoscope devices were still in common use through the 1940s, offering customers a �peep-show� for a penny, or a nickel in later decades. You can still take a trip down memory lane with one if you waltz into the Penny Arcade on �Main Street USA� at Disneyland, where the devices run for the novel price of a penny!

Another improvement in the industry was Cinematographe: the world�s first portable motion camera, unveiled by Louis Lumiere in 1895. This baby not only was succeeded by Edison�s Videoscope (or Projecting Kinetoscope) only a year later, but both provided the solid foundation of the modern movie theatre.

The next big hurdle in filmmaking was how to transfer the content of the theater to the living room. It took decades before the average Joe could sit down in front of the TV with a frozen dinner and watch something out of a box, instead of over the airwaves.

In 1965, you could own an RCA Video Tape Recorder (VTR), which stored monochrome images on 2.5� tapes for slightly less than $1000. That�s over $6000 in today�s money. It wasn�t until 1978 when you could walk into an electronics store and purchase a video recorder without breaking the bank to do so, though the cost at the time was certainly not like a trip to McDonald�s. The biggest choice to make then, and throughout the early 1980s was JVC's VHS format, or Sony's superior BetaMax . The latter of the two sadly died off due to loss of market share and strict distribution methods.

Parenthetically, home VCR sales were initially mainly driven by umm, shall we say, "adult" films on tape.

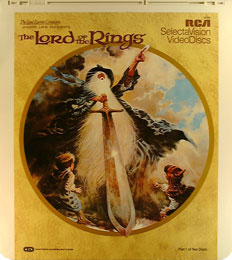

Videodisc formats followed their tape-based cousins soon thereafter, with the release of RCA's SelectaVision, a rather oddball format quite similar to a phonograph record where a needle actually rode in the grooves of a disc whose surfaces were so fragile the disc lived inside an enormous cartridge, and the superior MCA DiscoVision (LaserDisc).

The former, short lived, SelectaVision platform (A.K.A. CED) lasted for a whopping three years, while the LaserDisc format is still available today (at a price) for those movie buffs out there who still love the fledgling format. A friend of mine is a LaserDisc fanatic who owns a few high-end decks and probably over a thousand movies in that format.

Naturally, following this marketing war, the new era of digital video began to emerge from the shadows of tapes and discs, leading up to the MPEG format, and eventually to the DVR / PVR (Digital / Personal Video Recorder).

Products such as the TiVo brought digital recording into your home, and the concept of a DVR became so solidified in our community that people now carry iPod Video models and similar appliances on their belts and in their cars.

Of course, you don�t need an iPod Video to watch your digital library on the go. All you need is your Treo, a little creativity and CorePlayer, the premier video player for PalmOS.

Until recently, if you wanted to watch movies on the go, or in-flight, you had to shell out beau coups bucks to do so, either by purchasing a laptop with DVD playback capabilities, a portable DVD player, or some other, overpriced gadget to play your videos.

Apple broke the monotony with their iPod product line when they introduced the iPod Video series, but the selection of formats it can handle are severely limited, and the internal capacity is forever restricted by the frail and expensive microdrives those ubiquitous 'pods use for storage. Just one shock, or drop, of the right velocity and all of those movies you bought through the iTunes store go away. Poof. Microdrives are built to such microscopic tolerances, it doesn't take much abuse to ruin one.

Thankfully, with your Treo in hand you can transplant your video library from the kludged devices of the past to your sleek and provocative smart phone via its built-in SD card slot. Just copy your files to a card, pop it in your Treo and bang(!) you're ready to go.

The only real limitation is video formats, as the software your Treo ships with only plays a few media types, though admittedly the 700p supports many more than the 650 did, including MPEG4, the Apple format which is ever-growing in popularity thanks to it being the default iPod media type.

What do you do if your files are not in the right format? You could spend countless hours converting them on your desktop machine, but doing so not only takes (seemingly) forever, but it also means that your system is all but dedicated to the CPU-intensive task. A better alternative is a player which automatically recognizes your entire existing library, and that�s precisely what CorePlayer does.

CorePlayer (CP), developed by CoreCodec of Palm Coast, Florida, is a tiny application with a host of support files for each kind of media format. Not only does it play back video files on your Treo, but it also supports a wide range of audio formats as well, so you can queue up a list of multimedia content and just sit back to enjoy the ride.

File types supported by CorePlayer are a veritable alphabet soup of acronyms and they include: MP3, MKA, WMA, WAV, OGG, Speex, WAVPACK, FLAC, AMR, ADPCM, ALaw, MuLaw, and MIDI audio files; and H.264 (AVC), MKV, MPEG-1, MPEG-4 (ASP), DivX, XviD, WMV , and MJPEG video formats. Video files may be in one of the following containers Matroska, TS, PS, 3GPP, MOV, AVI, MPEG-4, though raw file formats such as .mpg play just dandy.

Search for any of those acronyms in good old Wikipedia if you want to know more about them.

Copyright 1999-2016 TreoCentral. All rights reserved :

Terms of Use : Privacy Policy

TREO and TreoCentral are trademarks or registered trademarks of palm, Inc. in the United States and other countries;

the TreoCentral mark and domain name are used under license from palm, Inc.

The views expressed on this website are solely those of the proprietor, or

contributors to the site, and do not necessarily reflect the views of palm, Inc.

Read Merciful by Casey Adolfsson